Authors: Jack W. Scannell, Alex Blanckley, Helen Boldon & Brian Warrington

Synopsis

This is a very general review paper that gives potential explanations for the dramatic decline in the efficiency of drug development over the past few decades (in terms of # approved drugs per dollar spent in R&D). Three of the biggest reasons include the fact that (1) drugs must improve on previous drugs, making their development more difficult; (2) regulation has become more stringent, and (3) there is a shift toward molecular reductionism and target-based screening while our understanding of disease remains incomplete.

Summary

Background

In the past few decades, there have been huge advances in the technological aspect of drug development, including the number of molecules that can be synthesized per chemist, DNA sequencing throughput, X-ray crystallography throughput, computational drug design, etc. HTS made testing compound library against protein targets 10x cheaper since mid-1990s.

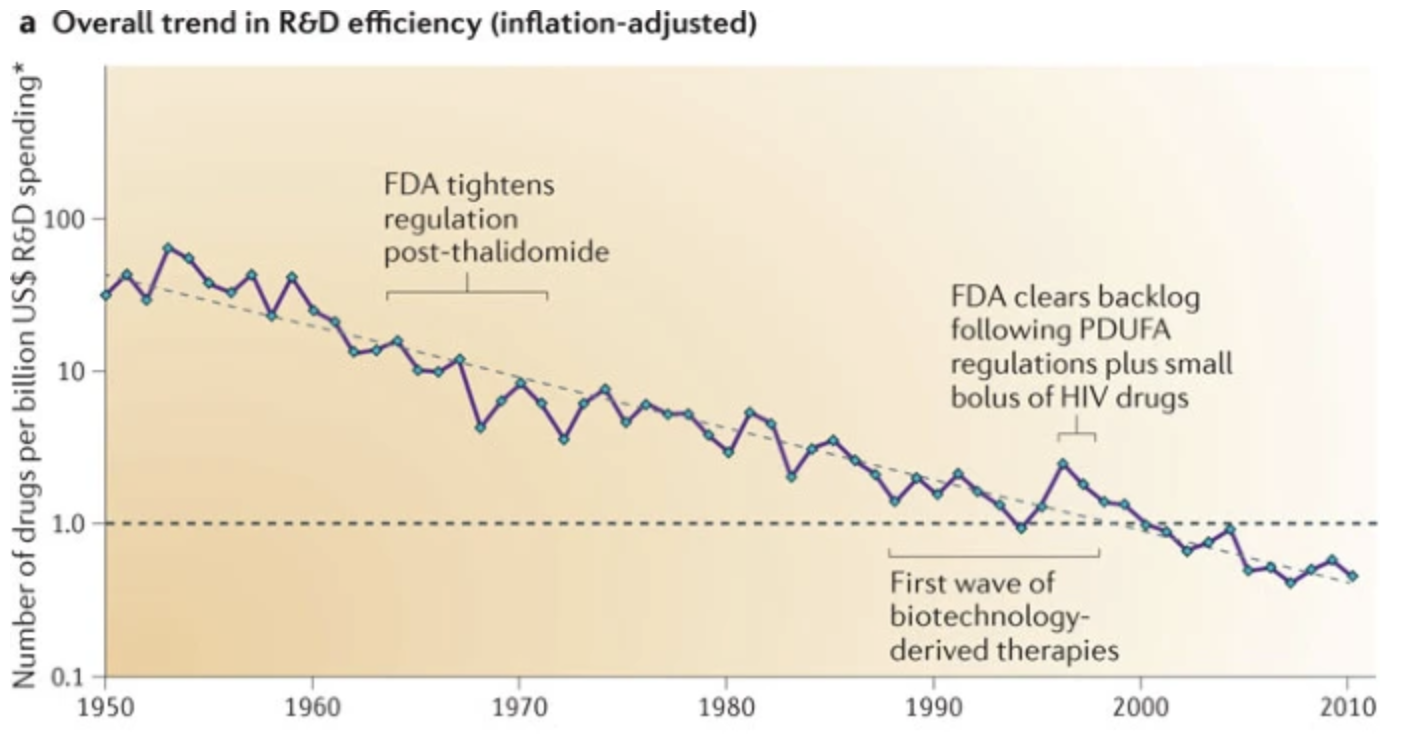

Yet, new drugs approved per billion US dollars spent on R&D (inflation adjusted) has decreased 80-fold since 1950. In other words, inflation-adjusted cost of bringing a new drug to market is doubling every 9 years. Why?

Figure 1. Trend in R&D efficiency over time.

“Better than the Beatles” problem

This problem stems from the fact that new drugs must be objectively better than previous drugs in order to be approved. From 1990 to 2004, R&D projects shifted from commercially crowded therapeutic areas with high historic drug approval probabilities (e.g. genitourinary drugs and sex hormones) to less crowded areas with low historic drug approval (e.g. anti-cancer drugs).

A related problem, the “low-hanging fruit” problem, proposes that easy drug targets have already been found. However, this may be tautological as “already discovered” is often equated with “easy to discover.”

“Cautious regulator” problem

This problem stems from the fact that drug regulation has tightened over time, and regulation does not loosen even if it’s not necessary. An example given is the Ames test for mutagenicity, which is probably not that useful but is still a regulatory requirement.

As a side note, this problem might actually benefit large companies since it raises the barrier to entry.

“Throw money at it” tendency

The problem stems from companies spending money in the wrong areas of R&D such as human resources (ouch).

“Basic research-brute force” bias

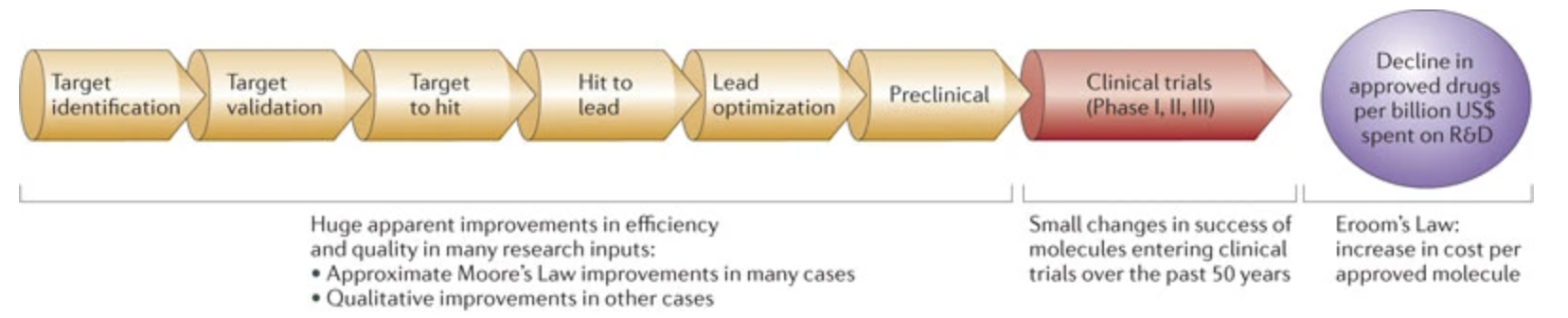

This problem stems from an overestimation of our understanding of molecular biology and brute force screening methods in simple assays. Although there exist many more potential drug targets (catalyzed by the genomics revolution), and HTS produces many more potential molecules, the probability that a small molecule successfully completes clinical trials has remained constant for 50 years. This means that these perceived improvements do not actually reflect in drugs that are safe and effective in humans.

The current thinking in drug development goes: high-affinity binding to a single biological target linked to a disease will lead to medical benefit in humans. This might be thought of as a case of “molecular reductionism.” How do we link targets to disease? Why single targets? We need to make the assumption that we know which proteins are directly involved in disease, and modifying activity via drugs will directly affect the disease. This is a very nontrivial assumption for many diseases.

Figure 2. Flowchart of drug development pipeline. Early stages of the pipeline have seem huge boosts in efficiency, but these do not translate to higher chance of success in clinical trials (which probably stems from our poor understanding of disease mechanisms).

In fact, more first-in-class small-molecule drugs approved between 1999 and 2009 were discovered using phenotypic assays than target-based assays. HTS involves the same collections of around 100,000 compounds (much fewer than the \(10^{26}\) - \(10^{62}\) possible drugs complying with Lipinski’s rule of 5). These collections are biased towards developable compounds with acceptable ADME (absorption, distribution, metabolism and excretion) characteristics. Moreover, compounds are initially screened for just potency, rather than full biological profile). Directed iteration may actually be more efficient. It is also important to keep in mind that virtually all approved drugs exhibit survivorship bias, in that each of these drugs had plausible mechanism and biological connection to disease, yet the vast majority of other drugs with similarly plausible mechanisms and connections to disease fail for unexpected reasons.

Biologics have a higher approval rate (32%) than small molecules (13%) from 1993 to 2004. This may be because monoclonal antibodies target cell surface proteins or extracellular signaling molecules, for which we might know the mechanism better.

“Narrow clinical search” problem

This problem stems from the fact that the drug discovery approach has shifted from looking broadly for therapeutic potential in biologically agents, to looking for precise effects from molecules designed with a single drug target in mind. In the 1950s-60s, initial screening was done in vivo rather than in vitro/in silico.

“Big clinical trial” problem

Clinical trials are increasing in size. This is probably partially a consequence of the “better than the Beatles” problem, which causes improvements to become smaller and requires larger clinical trials to determine them. Moreover, if a drug exists for an indication, then the new drug must be tested on top of existing drug a.k.a standard of care (SOC) for ethical reasons, since otherwise you’d be denying a person the best treatment.

“Multiple clinical trial” problem

The cautious regulator wants narrow indications, resulting in more clinical trials per drug.