Authors: Corbin Quick, Xiaoquan Wen, Gonçalo Abecasis, Michael Boehnke, Hyun Min Kang

Synopsis

This paper gives a nice summary of different ways to aggregate single-variant association statistics for gene-based tests. They propose a new omnibus test based on either the aggregated Cauchy association test (ACAT) or harmonic mean p-value (HMP).

Summary

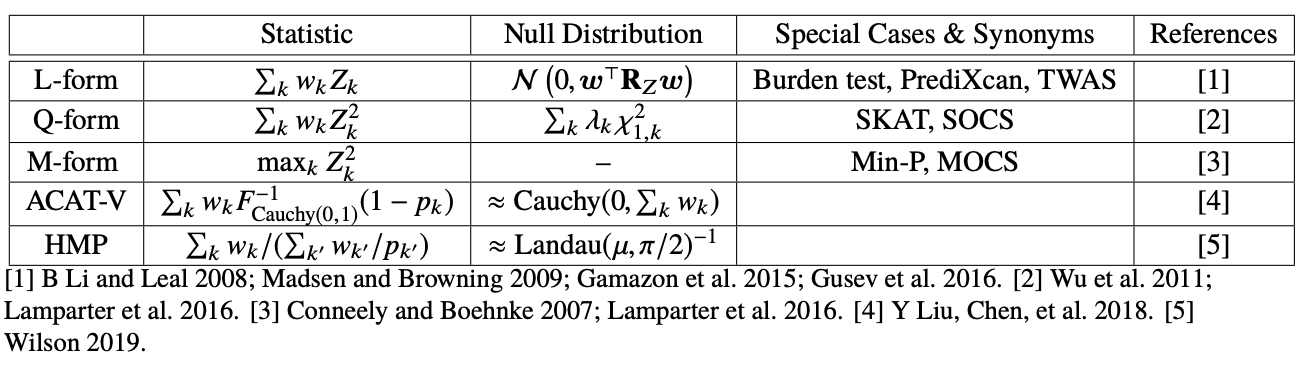

Table 1

This table summarizes different ways to aggregate single-variant association statistics. \( w \) represents a given SNP weight (can be eQTL effect size or other arbitrary weight), \(Z \) represents a given SNP effect size, and \(p \) represents a given SNP p-value.

L-form: This form takes a linear combination of single-variant association statistics in a region. It relies on prior knowledge regarding direction of effect across variants. It includes burden tests (which assumes that rare variants all increase risk for disease) and TWAS (which assumes that the effect on gene expression is the same direction as the effect on the trait, i.e. mediation).

Q-form: This form takes a linear combination of squared single-variant association statistics in a region. It works well when many variants have non-zero effects of unknown direction.

M-form: This forms takes the max squared single-variant association in a region. It works well when small fraction of variants have non-zero effects.

ACAT-V: This form applies the aggregated Cauchy association test, which is a way to combine multiple dependent p-values. It works well when a small fraction of variants have non-zero effects.

HMP: This form applies the harmonic mean p-value, which is a way to combine multiple dependent p-values.

GAMBIT omnibus test: This is an omnibus test that combines p-values from all tests using ACAT or HMP.

Some thoughts

The whole idea behind gene-based tests is to test for total nonzero effect of a given region in the genome on the trait. If we add up the squared effect sizes of SNPs without weighing, we will estimate the heritability of the region. If we weigh the SNPs in some manner, we will no longer be estimating heritability. However, we can still calculate the null distribution of the weighed SNPs (i.e. what the statistic will look like given that all SNPs have zero effect), so we can still test the hypothesis that the region has total nonzero effect.

There is an important distinction between a SNP simply having nonzero effect vs. caring about the actual value of the effect. The latter weighing scheme can increase power to detect nonzero effect at the expense of the actual value of the effect being not related to heritability. For example, compare the following hypotheses: \( \beta_1^2 + \beta_2^2 = 0 \) and \(a_1\beta_1^2 + a_2\beta_2^2 = 0 \). The first hypothesis tests that the heritability of the two SNPs is nonzero. The second hypothesis tests that some quantity is nonzero. Suppose that \(\beta_1\) and \(\beta_2\) are both 0 in reality. Both tests will have well calibrated false positive rates. Now suppose that \(\beta_1\) is 1 and \(\beta_2\) is 0 in reality. Let \(a_1\) = 2 and \(a_2\) = 1. The second test is more likely to reject the null hypothesis than the first. Thus, we have more power to detect nonzero effects of SNPs within the region.

What about identifying individual SNP associations? We weigh SNPs that we believe are more likely to have an association. Is it possible to have false positives under this weighing scheme? Yes, which is why we need to do simulations to confirm that FPR is controlled.