Author: Pedro Domingos

Synopsis

This paper describes 12 rules about machine learning that the author calls “folk knowledge,” in that they are well known to experienced machine learning practitioners but not readily found in textbooks.

Summary

(1) Learning = Representation + Evaluation + Optimization

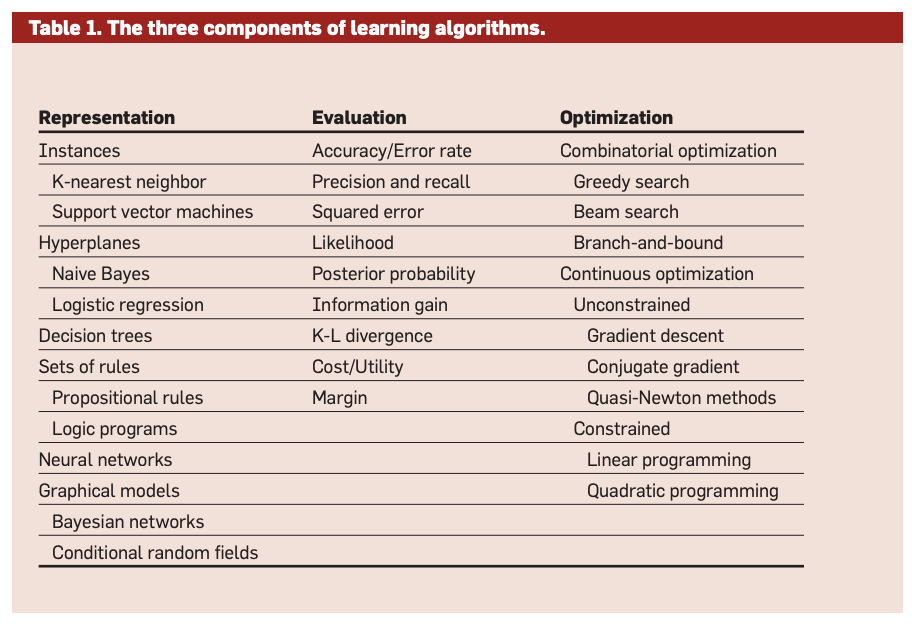

Machine learning consists of combinations of the following three things:

- Representation. A classifier has a hypothesis space, representing all possible classifiers of that type that can be learned.

- Evaluation. An objective function is needed to tell the classifier how good it’s doing.

- Optimization. There needs to be a way to search among the classifiers in the hypothesis space that give the highest score according to the objective function.

Basically, for a given application of machine learning, you pick one thing from each column of the following table:

(2) It’s Generalization that Counts

Generalization (prediction beyond the training set) is the ultimate goal of machine learning. As a result, it is crucial to make sure training and test data are separate. Sometimes, it can be hard to tell when test data are contaminated with training data (if for example test data is used to tune parameters).

We don’t actually have access to the function we want to optimize in order to minimize generalization error, so we use training error as a surrogate for test error. On the flip side, since the objective function is a proxy for the true goal, it often does not need to be fully optimized.

(3) Data Alone is Not Enough

There will never be enough data to learn all possible classes from a set of variables. In addition, the no free lunch theorem states: for every learner, there exists a function from data to class for which random guessing will be better than the learner. However, functions in real data are not drawn uniformly from set of all functions. Even general assumptions like smoothness and similar examples having similar classes are enough for machine learning to be successful.

One of the key criteria for choosing a representation is which kinds of knowledge are easily expressed in it. Our knowledge is hard-coded into the choice of representation. Learners combine knowledge with data to grow programs.

(4) Overfitting Has Many Faces

Generalization error can be decomposed into bias and variance. Different learners will trade off bias and variance.

Cross-validation can combat overfitting but can itself lead to overfitting if it is used to make too many parameter choices. Regularization penalizes classifiers with more structure, thereby favoring smaller ones with less room to overfit.

(5) Intuition Fails in High Dimensions

Classical distances (like Euclidean distance) become weakly discriminant when we have multidimensional and sparse data (curse of dimensionality), i.e. the ratio between the nearest and farthest points approaches 1 as the dimensions increase.

Extra dimensions add noise; if you have a lot of useless attributes, Euclidean distance will become useless. However, if you could easily embed your data in a low-dimensional data space, then Euclidean distance should also work in the full dimensional space (see stackexchange here).

Generalization correctly becomes exponentially harder as the dimensionality grows since the training set covers less of the input space.

In high dimensions, most of the mass of a multivariate Gaussian distribution is not near the mean, but in an increasingly distant “shell” around it; and most of the volume of a high-dimensional orange is in the skin, not the pulp.

The “blessing of non-uniformity” states that examples are not spread uniformly throughout instance space but concentrated on a lower-dimensional manifold.

(6) Theoretical Guarantees Are Not What They Seem

Most bounds are very loose. If learner A is better than learner B given infinite data, B is often better than A given finite data. The main role of theoretical guarantees in machine learning is not as a criterion for practical decisions, but as a source of understanding and driving force for algorithm design. Just because a learner has a theoretical justification and works in practice does not mean the former is the reason for the latter.

(7) Feature Engineering is the Key

Learning is easy if you have many independent features that each correlate well with the class. It is hard if the class is a very complex function of features. Machine learning is not a one-shot process of building a dataset and running a learner, but rather an iterative process of running the learner, analyzing the results, modifying the data and/or the learner, and repeating. Feature engineering is the most time consuming part of a machine learning project. You could try automating feature generation, but it’s hard to assess all combinations of features.

(8) More Data Beats a Cleverer Algorithm

Machine learning is all about letting data do the heavy lifting. In most of computer science, the two main limited resources are time and memory. In machine learning, there is a third one: training data. Which one is the bottleneck has changed from decade to decade. In the 1980s it tended to be data; today it is often time.

All learners essentially work by grouping nearby examples into the same class; the key difference is in the meaning of “nearby.”

It pays to try the simplest learners first. Learners can be divided into those with fixed size representations (like linear classifiers) and those whose size grows with data (like decision trees). Fixed sized learners can only learn so much from data. Variable sized learners can in principle learn any function but in practice often can’t due to limitations of algorithm or computational cost.

(9) Learn Many Models, Not Just One

The best learners often comprise a bunch of models in an ensemble. Techniques for combining models includes:

- Bagging. For this technique, you resample training set, learn a classifier on each, and combine results by voting. This greatly reduces variance while only slightly increasing bias.

- Boosting. Training examples are weighted so that each new classifier focuses on examples the previous ones got wrong.

- Stacking. For this technique, outputs of individual classifiers become inputs of a higher level learner.

Ensembles outperform individual learners. However, this is different from Bayesian model averaging (BMA), which averages the individual predictions of all classifiers in a hypothesis space weighed by a prior and how well they perform on training data. Ensembles change the hypothesis space, while BMA doesn’t.

(10) Simplicity Does Not Imply Accuracy

There is no necessary connection between the number of parameters and tendency to overfit. The size of the hypothesis space is only a rough guide to what really matters for relating training and test error: the procedure by which a hypothesis is chosen. A learner with larger hypothesis space that tries fewer hypotheses is less likely to overfit than one that tries more hypotheses.

(11) Representable Does Not Imply Learnable

Many representations carry theorems that go like: “every function can be represented arbitrarily closely using this representation.” This is useless if there is no way to actually learn the function.

(12) Correlation Does Not Imply Causation

If machine learning is applied to observational data, probably no conclusions about causality can be drawn.